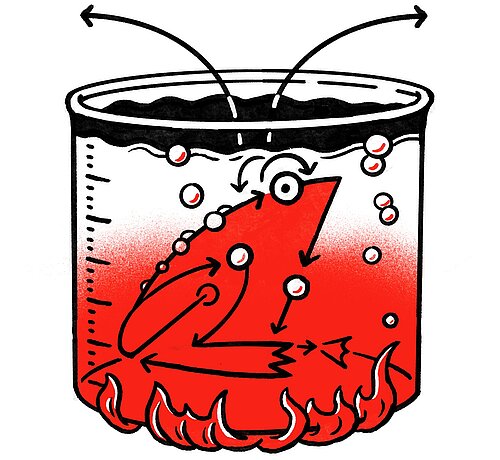

Why is it so difficult to motivate action in the face of climate change? Imagine a lobster in a slowly heating pot of water. Until recently, climate change for Western society in the northern hemisphere was a very gradual and statistical phenomenon. We hardly notice it. So, before we know it, we're boiling, although we never had the experience that we are in danger. Just like the lobster in the pot. When do we make the decision to jump out and get active?

I am fascinated by understanding how people respond to changes in their environment. How they adapt or fail to adapt to those changes, especially when it comes to phenomena with long time horizons that are outside of our evolutionary experience, like climate change.

Historically, we seem to be an amazingly successful species. But there are limits to our success. We may soon be reaching the boundaries. I want to help people transcend the difficulties in adapting to the changing circumstances. Science, for me, has the purpose of making things better for people and for other species.

I was trained as a cognitive psychologist, looking at how the mind works, and as a mathematical psychologist, modelling behavior to simulate what people do, and predict what they might do. I also use theories and tools of social psychology, asking for the motivation behind human behavior: What triggers people to do something? What motivates them to make changes in their lives?

Human decision-making processes are influenced by different factors. We usually identify three camps: calculation-based decisions, which are rational, emotion-based decisions, if we do something out of fear, guilt or hope for example, and rule- or role-based decisions that have to do with our perceived social role and the fact that we are social animals. In my lab, we are trying to understand how these different decision processes fit together and how they can be used to make better decisions in the sense that we do not regret them in the long run.

If we think about personal decisions to reduce carbon emissions for example, a calculation-based decision process would probably not lead to change. If I am trying to decide to change from a meat-based diet to a plant-based diet for example, the switching costs seem high and potentially ineffective if everybody else keeps eating meat. Fortunately, homo sapiens also does things as a social animal. We care for other people, our children, grandchildren, and future generations.

If I see that other people are starting to change their behavior, there might be a dynamic shift in norms. Eating meat might no longer be seen as a cool and natural thing to do, but as something that destroys our planet. It is not necessary that everybody is switching at once. The tipping point usually lies around 35 percent. So, as a policy maker, it might be a good idea to subsidize a significant minority to do the right thing for the tipping phenomenon to kick in.

In my Einstein project, I am comparing the urban context in Berlin with the rural context of Brandenburg. We want to approach local policymakers to find out what they identify as barriers for interventions that are both good for their citizens now and for people in further away places in the long run. We want to help them overcome the difficulties of decision-making towards long-term climate policies.

We will also do a country level comparison on this kind of decision making in the context of climate change. We will look at how norm-based interventions work in Berlin versus New Jersey in the U.S, and New Delhi in India, which all have very different norms and stages of public awareness. This will show us how decision processes for climate interventions depend on the economic and social environment and how we can redesign choice environments for local contexts to take on global climate goals. My hope is that our research can contribute to making those climate goals more realistic, starting at a local level. And finally make the lobster jump out of the pot.