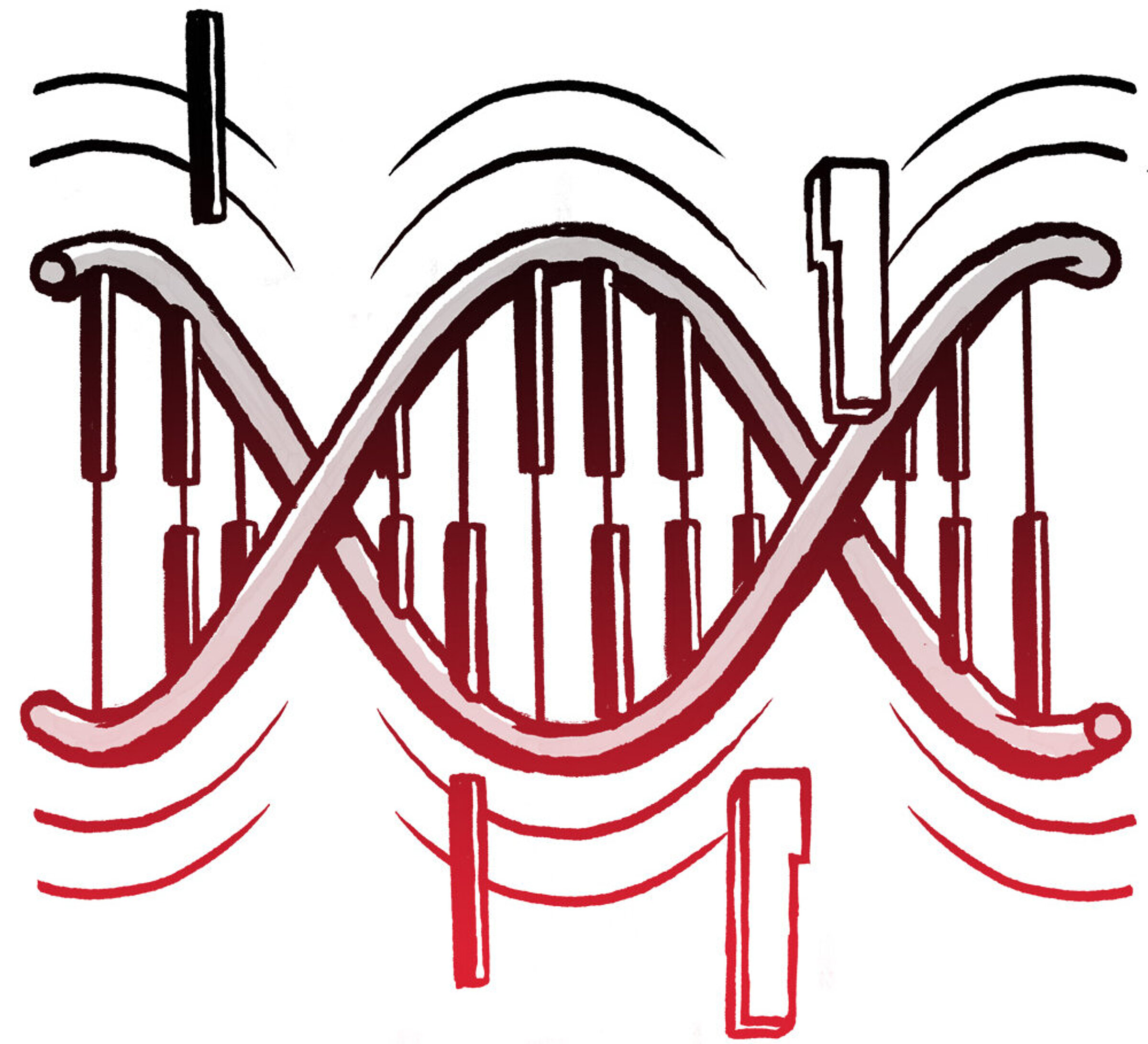

Imagine you are playing a piano concerto. If you removed a couple of keys, you might get through the piece, but sometimes the sound would be excruciating. That is what can happen with gene activation during brain development. We all have our keys given to us at our conception and often we get through our “concerto” of life without major difficulties, but sometimes life can be devastating if one particular key is missing. Altered expression of a single gene can have disastrous consequences on brain development.

I am looking into how the components of our nervous system are born, migrate, are assembled, and fine-tuned to perform their functions. I am also examining how their interconnections remain plastic and how they are removed when they are no longer needed. I want to understand the extent to which the different computational functions of the brain are determined by the unfolding of the genetic program and modified by the environment. As our brain develops, our whole life experience gets embedded in its structure, especially in the cerebral cortex. Our experiences shape our brain – how many languages we speak, whether we play tennis, use our right or left hand.

Unlike a computer, the brain is being constructed while it is already switched on and it is running programs that are essential for its own assembly. During the creation of the neural circuits, a cell type called the “subplate” is present early on in our development which helps build the more permanent circuits. In a way, these cells function as transient dynamic scaffolds. They are also the first recipients of input into the cerebral cortex and start to process the information when the rest of the brain cells are not even born. When their work is finished they largely disappear. But in people with a cognitive problem, for instance, schizophrenia, autism or epilepsy, many more survive.

Neurodevelopmental disorders are extremely important to study because they can have a huge impact on the entire life of the individual and their families. We need basic science to understand the mechanisms. The developing brain is not just a smaller version of the adult brain; it is a completely different structure with different rules. In Berlin, we are trying to understand what the consequences are if the “subplate cells” persist in larger numbers. This will help us to start linking problems with these persistent cells to cognitive dysfunctions.

Some of the keys on the piano are only needed at the earliest stages of our “concerto of life” in the developing brain, but they are essential to establish melodic, harmonic or rhythmic material key to the rest of the piece. Over millions and millions of years of selection, we have evolved this extremely powerful, awesome computational device that is so well suited to generate creativity in art and science – provided we have all the keys and the right input from the earliest stages of its development. The rest depends on what we use it for.